Windows 8 Development for Force.com – Part 1, OAuth 2.0

This is the beginning of a multipart series on developing Windows 8 mobile apps for Salesforce.com with the user interface design language that was–until recently–referred to as Metro UI. Though the name is now Windows 8 UI, the typography-based design principles are the same, and you can read more about them in my April 30 blog post.

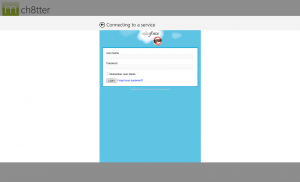

Over the course of this series, we’ll be developing a simple Chatter client for Windows 8 ![]() , shown below. The code for this is on GitHub, so feel free to follow along there. Part 1 covers how to log into Salesforce.com (or Database.com) and maintain a connection using OAuth 2.0, an industry-standard secure authentication mechanism. OAuth is the preferred mechanism for logging into SFDC from mobile or web apps, and if you haven’t seen it used in a business app before, you’ve almost certainly used it to log into a mobile app using your Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn credentials. One of the primary benefits of using OAuth in mobile apps is that the actual login dialog is hosted by the service provider, so the user never enters their username or password directly into the application itself. As you can see in the screenshot above, the actual login screen is shown within a webview, and carries the Salesforce.com branding so the user knows what service they’re logging into.

, shown below. The code for this is on GitHub, so feel free to follow along there. Part 1 covers how to log into Salesforce.com (or Database.com) and maintain a connection using OAuth 2.0, an industry-standard secure authentication mechanism. OAuth is the preferred mechanism for logging into SFDC from mobile or web apps, and if you haven’t seen it used in a business app before, you’ve almost certainly used it to log into a mobile app using your Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn credentials. One of the primary benefits of using OAuth in mobile apps is that the actual login dialog is hosted by the service provider, so the user never enters their username or password directly into the application itself. As you can see in the screenshot above, the actual login screen is shown within a webview, and carries the Salesforce.com branding so the user knows what service they’re logging into.

Logging into Salesforce.com from a mobile app and maintaining that authentication so that the user doesn’t have to log in every time the session expires requires the implementation of two separate OAuth 2.0 flows. The User-Agent Flow handles the initial login to the app, and the Refresh-Token Flow handles refreshing the session key (the OAuth Access Token) whenever it expires. The expiration timeout value is configurable from within Salesforce setup to between 15 minutes and 12 hours.

Salesforce.com Setup

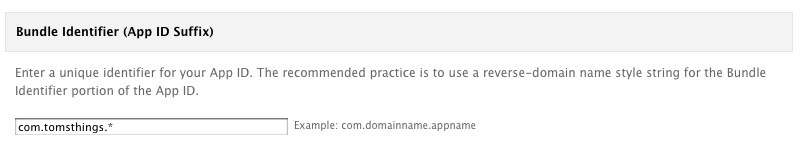

The first thing you’ll need before you begin on the mobile app is a Consumer Key and a Callback URL (also referred to as a Redirect URI) from your Salesforce org. For information on how to get these from Remote Access configuration, take a look at the Salesforce Configuration section of my OAuth 2.0 for Salesforce.com blog post.

User-Agent Flow

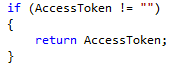

We’ll start out with the User-Agent flow to get an initial login to the app. To start, take a look at SFDCSession.cs in the GitHub repository. This class is a singleton that’s used to maintain session state throughout the app. Any class throughout the app can access the session information with the SFDCSession.Instance static accessor method. You’ll see the AccessToken and RefreshToken are defined as empty strings, and the ConsumerKey and RedirectUri are defined to match the remote access information in my SFDC developer org (you’ll just have to believe me on that one). The User-Agent flow is implemented using the oAuthUserAgentFlow() method in this class.

The first thing I’ve done in oAuthUserAgentFlow() is check to see if we already have an AccessToken. That way if the method gets called twice for some reason, or if a developer wants to hard-code an Access Token to speed up development, it will just skip over the rest of the method, and return the Access Token to the calling function.

Next, we check to see if we have a Refresh Token persisted in the encrypted PasswordVault from a previous run of the application. Since the Refresh Token can be used to generate Access Tokens to Salesforce.com, it’s important to treat it as secure data, and encrypt it accordingly. The RefreshToken getters and setters handle storing and retrieving the refresh token with vault.Retrieve() and vault.Add().

If we are able to retrieve a Refresh Token from the PasswordVault, then we can use the Refresh Token flow (which we’ll cover in a bit) to get a new Access Token.

One thing you’re seeing here that you may not be familiar with if you’re not already a C# programmer is the await keyword. To use await, you need to declare the method as async. This is a simple way to launch an asynchronous operation without blocking the UI thread. Since both the Access Token Flow and the Refresh Token Flow are network operations that call out to Salesforce.com endpoints, it’s necessary to use await in order to keep the application responsive to user interaction while the network operation is happening in the background.

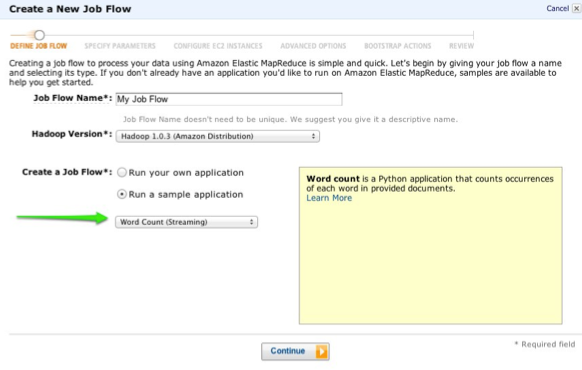

If we don’t have a Refresh Token stored, this is either the first run of the application, or the user has previously logged out of their session, so we need to present the login dialog. Microsoft actually makes this fairly straightforward using WebAuthenticationBroker and some related classes. First, we need to define our request URI. This is the HTTP GET request that we send to Salesforce to request the login dialog be displayed to the user, and it comes in this format:

https://login.salesforce.com/services/oauth2/authorize?

response_type=token&

display=touch&

client_id=[CONSUMER KEY]

redirect_uri=[REDIRECT URI]

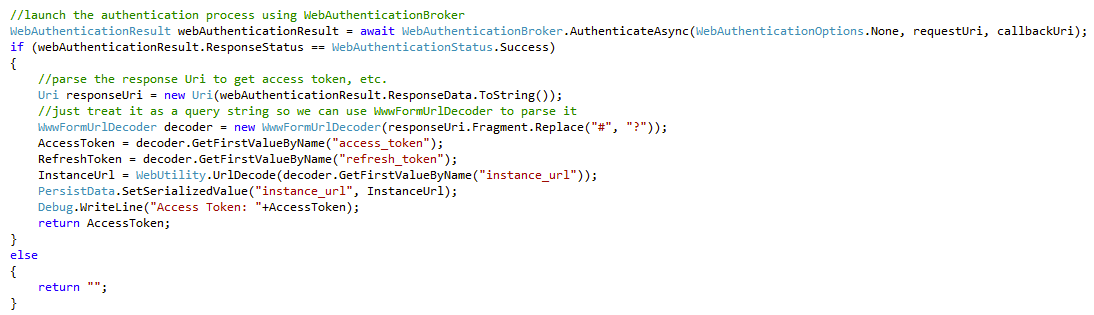

Into this, we plug our Consumer Key and WebUtility URLEncoded Redirect URI from our Salesforce.com Remote Access settings (or Connected Apps if you’re using that instead — as of the Winter 2013 release, Connected Apps is in Pilot release). We can then call the AuthenticateAsync method of WebAuthenticationBroker with our Request URI and our Callback URI. This returns an object of type WebAuthenticationResult. First we check to make sure the ResponseStatus is successful, and if it is ResponseData will contain the response URI from Salesforce.com containing our Access Token, Refresh Token, the Instance URL we should use for calls to the Force.com REST API, and some other information like the Org Id and the logged-in User’s Id. We save all of this information, and the RefreshToken setter stores that piece of important information in our PasswordVault. The Instance URL isn’t a secret, but it is useful to keep around, so we save it using the ApplicationData class, which gives us simple key/value storage that can be easily and automatically synchronized between Windows 8 systems.

At this point, we have authenticated, and we have all of the information needed to query the Force.com REST API or the Chatter REST API. We’ll get to how exactly we do that in Part 2 of this series. But first, we need to implement the Refresh Token Flow so that the app can reauthenticate behind the scenes when the Access Token expires.

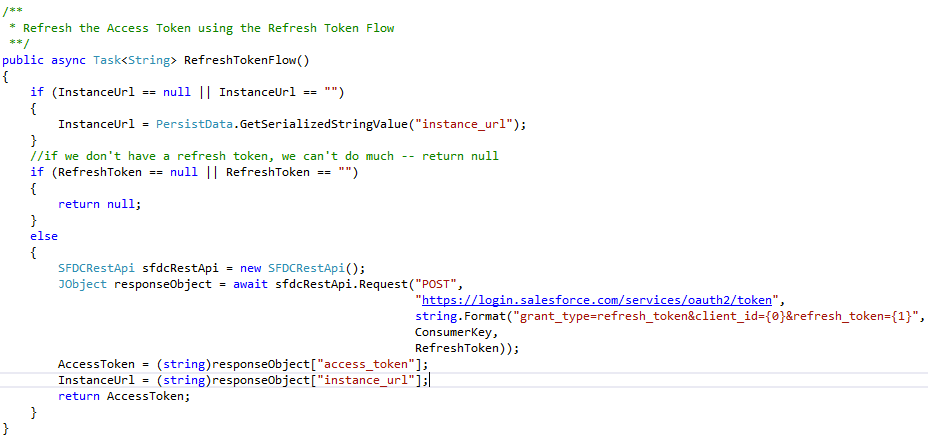

Refresh Token Flow

Compared to the User-Agent Flow, the Refresh Token flow is pretty simple. It doesn’t require the user to do anything, so it can happen asynchronously behind the scenes whenever the app launches or if the REST API returns an HTTP 401 Unauthorized response to a query. The flow requires an HTTP POST request be sent to login.salesforce.com using these parameters:

Method: POST

URI: https://login.salesforce.com/services/oauth2/token

Parameters: grant_type=refresh_token&client_id=[CONSUMER KEY]&refresh_token=[REFRESH TOKEN]

If successful, the response from Salesforce returns a new Access Token and a new Instance URL. It’s possible — though unlikely — that your Salesforce.com org will have changed from one server instance (na1, na2, etc.) to another since the last login, so it’s a good idea to update both.

Anyway, that’s it. Be sure to check back for the next part in this series, where we’ll dig into querying the Chatter REST API, and showing the feed in the UI.

One million tweets per day.

One million tweets per day.

.png)

.png)